The Train Station

The following is but a taste of Le Musée d'Orsay history, but for even a taste, we have to start with the train.

The train ushered in an era that upended all previous notions of distance and speed. Its invention connected isolated towns and villages, integrating them into urban conglomerations, bringing massive influxes from the countryside into the capital (itself in upheaval from Haussmann’s rebuilding) and turning it into a hugely populated city of immigrants from the other corners of France and beyond. As early as 1851, the city’s inhabitants boomed, doubling to 1.2 million in fifty short years and thirty years later, in 1881, to 2.2 million, more even than today’s 2.1 million.

By the 20th century’s dawn, the City of Lights inaugurated a new line connecting it with Orléans and points southwest. Like all railways, it promised progress, a whole new era symbolized by that year’s 1900 Exposition Universelle.

The new station, across the Seine from the Louvre by way of the Pont Royal, had to vie with its neighbors, so the pared-down minimalism coming into fashion at the time just would not do. The patrons chose the opulent Beaux-Arts style for an old-fashioned stone work exterior. Its ornate decoration hearkened to classic French structures of another age (it would go on to inspire New York’s regretted Penn Station) and was in fact meant to disguise technological advancements. The choice was a far cry from the form-follows-function style that was soon to become architectural orthodoxy. To see the more typical marriage of then-modern-day steel and glass, you had to enter the train shed, where the platforms and passenger concourse stretched over 16 different lines.

When those same advancements meant that trains become too long for the Orsay train shed, the station slowly fell into disuse, even dereliction. By 1945, for instance, it worked as a holding station for prisoners of war returning from Germany and even later Charles de Gaulle would use it as backdrop to press conferences in the 1950s.

The Museum

By the end of the 1970s the Centre Pompidou had opened to showcase 20th Century art, with the Louvre bursting at the seams. There had long been talk that the 19th, the segue between the Louvre’s old masters and the present, needed a space of its own. What better inspiration to house it than the lonely old Gare d’Orsay? As a train station it was the symbolic heart of what made Paris as we know it, the gigantic populous city exploding with art and creativity. Thus in December, 1986 the Musée d’Orsay opened to the public.

The curators chose to display creations from between 1848 (when Revolutions broke out in Paris and across Europe) and 1914 (beginning of the Great War). Thus, it contains a “mere” 3000 pieces of art compared to the Louvre’s 35,000 (from antiquity to 1840), but easily rivals that grande dame in popularity. You can easily see why with the following few picks from Memories’ favorites. We’ve focused on painters whereas the museum holds furniture, decorative arts and more, including sculpture, benefiting from that glass-and-steel overhead that once lit up the trains below.

Twenty Must-See Painters at the Orsay Museum

Once again, you’ll get so much more out of this museum with one of our guides. Especially with the museum’s popularity. In the crush of other visitors a little-known masterpiece can be missed in the blink of an eye. We can show you the highlights, the must-see art. More than that, you'll get the backstory on these incredible artworks and the artists who created them, insights that will make you see and understand them in a completely different light. And with us you can skip the lines, spending your precious hours marveling at art rather than waiting to buy tickets. And if you book a morning tour, that leaves you to be able to explore this masterpiece funhouse on your own whim, rich with the knowledge you’ll have culled from your guide’s introduction.

TWENTY ARTISTS STARRING AT THE ORSAY (FROM THE FAMOUS TO THE BEST-KEPT SECRETS)

First, to really get the full sense of what the rebellion of 19th Century art is all about we have to know about the Academy. This behemoth of an institution, with its biennial Salon, set all official artistic standards by the lights of the Old Masters. Or at least how they saw the old masters, far less experimental than they actually were. You’ll find examples of this art all over the museum.

Don't just rush up to the 5th floor to see the Impressionists. It's only by seeing and understanding what went just before them that you can truly appreciate how daring and different they were at the time. Keep reading to learn what to see at the Musée d'Orsay and in what order!

Thomas Couture Romans of the Decadence, 1847

photo: Google Art Project (Wikipedia)

One of the more famous paintings at the Musée d'Orsay, this enormous show stopper débuted at the Salon, the year before the revolutions of 1848 (the very reason of the museum’s opening choice of scope). It does tug at your heart strings with its precisely defined image of innocence compromised by moral decline. It’s certainly a criticism of Empire, but does it really offer food for thought beyond facile moralizing? Something to really sink your teeth into? Isn’t it a bit over the top? Artistically conservative, Couture might be painting in the very style of his subject matter, as though art must be frozen into an ideal of perfection that should never be questioned.

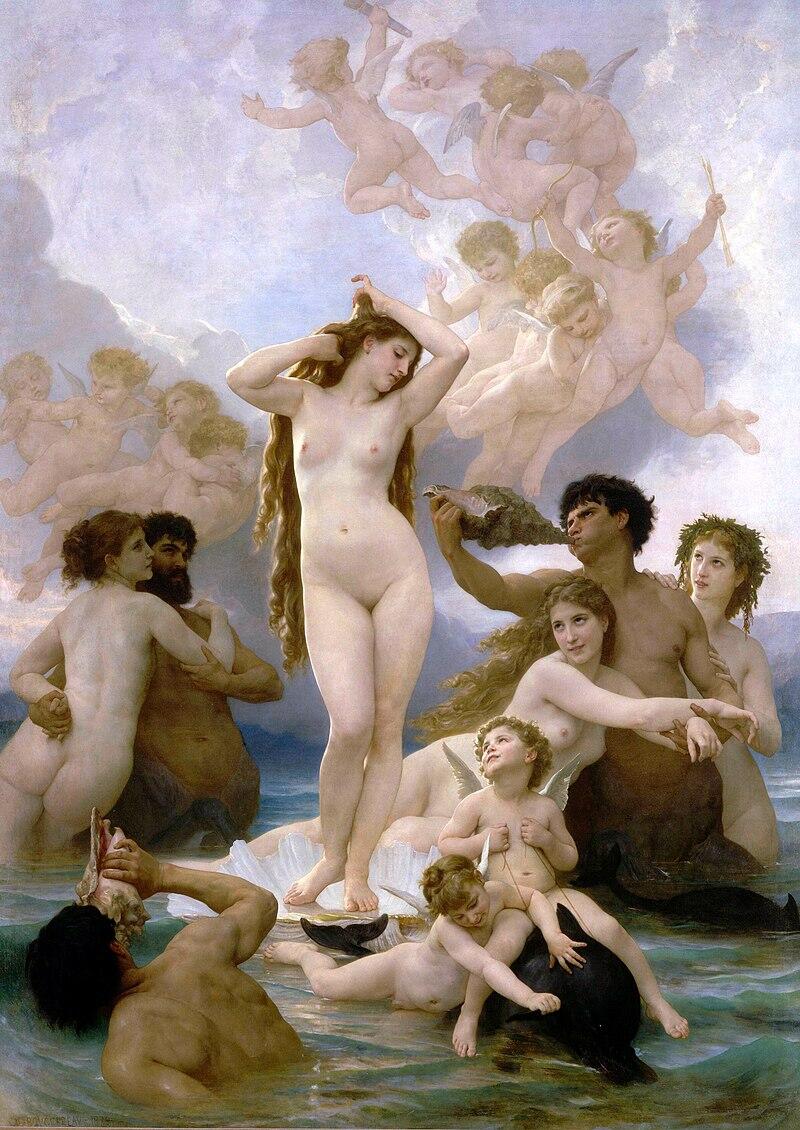

William Bouguereau Birth of Venus, 1879

photo: Musée d’Orsay (Wikipedia)

Here we are, over thirty years and two or so revolutions later, yet you’d never know it. Nothing much has changed, and that is the point. Venus is beautiful, in a highly finished, classic way, while the avant-garde Impressionists are precisely contemporary to this painting. Bouguereau shows quite simply the birth of the goddess of beauty and love as she had been portrayed countless times over the centuries before, with great technical skill, but, above all, tradition.

Jean-François Millet The Gleaners, 1857

photo: Google Arts and Culture (Wikipedia)

What a world away from either is this image, ten years after Couture. A Musée d'Orsay must-see painting, this is not classical shepherds living a country idyll. Instead, it shows women of the present, whom feudal tradition “generously” allowed to hand-pick through the already harvested wheat in order to make some bread for their starving families. This meant a day’s toil killing your back, bent over to collect enough minuscule stalks of grain to make a mere loaf for a whole pre-birth control family. Furthermore, not ten years before, Marx’s Manifesto scared the be-jeezus out of all comfortable Parisians, the ones frequenting these art shows, identifying more with the landholders than the working poor. Might these women be not so much scavenging as symbolically sowing the seeds of revolution, the very revolutions of the wealthy had suffered and survived in 1789, 1830 and 1848?

Edouard Manet

Olympia, 1863

Classically trained, precisely under Thomas Couture (who threw him out for painting clothes on the nude models) Edouard Manet was a man about town and Realist painter, who loved city life and all it represented of the modern world, even its rotten underbelly, which he explored while both honoring and taking the mickey out of those same old masters.

photo: Google Art Project (Wikipedia)

She is almost a parody of the long tradition of the reclining female nude, as modeled by what they called the “Grandes Horizontales”, the deluxe sex workers of the era. This one knows the whole exchange between the two of you is all about money and power. Notice behind her, Laure, one of the many immigrants of color creating a Black working class in Paris after the 1848 Abolition. She leans forward, as if whispering counsel to the courtesan when the look on the latter’s face seems thoroughly unimpressed with the bouquet brought in homage. A posy is not going to move either heart or that hand.

Déjeuner sur l’Herbe, 1863

photo: wartburg.edu (Wikipedia)

This image takes Titian’s Concert Champêtre (see our Louvre blog entry or tour) and gives it a modern, humorous twist. Two bohemian students live it up in one of Paris’s suburban woods, noted for its flora and fauna, and among that fauna are ladies of light virtue, instead of Titian’s muses. The face of the woman looking straight at the viewer has an expression that only modernity could have created in a great, vast city: the blank stare of looking towards a complete stranger without seeing them, such as graces every face on the Paris métro.

Edgar Dégas Fin d'arabesque, 1876-1877

Dégas was another well-to-do Realist like Manet, fascinated by the modern world.

photo: Alonso de Mendoza (Wikipedia)

The painter explores his interest in movement, especially quick, graceful precarious movement, as this ballerina finishes her pas with a flourish, although you must ask yourself, who exactly is she performing for, so personally? Is she not appealing to someone clearly in an expensive balcony seat watching her? A patron? A lover? A client? Are we really so far removed from his friend Manet’s Olympia? Not when you consider the life of a Belle Epoque ballerina and what it took to survive economically as a woman artiste of that era in Paris.

The Impressionists

Parallel to these two Realists were the Impressionists that flocked to them, with entirely reciprocal admiration. Today, over the century and a half since their first exhibit in 1874, there has been a progressive of Hallmarkization that has de-fanged the Impressionists for generations, with their soft focus straight out of those Merchant Ivory films portraying much the same era. But these painters’ diffuse dabs of light were in fact resolutely modern –chasing after the fleeting effects of time. If it’s the very instant you’re trying to portray, you cannot have the same kind of finish that we saw in Couture and Bouguereau. Moreover, this generation liked to paint directly from the outside world, while IN the outside world. The invention of the tin paint tube in 1841 allowed artists to venture out of their studios and do just that. Without that invention you can’t have Monet, who gave the school its name, chasing after the infinite moods of haystacks or cathedrals, their different aspects in moment-by-moment light changes, with someone to hand him a new canvas at each juncture, not even so much as finishing the one before.

Claude Monet

Gare St Lazare, 1877

photo: 0x010C (Wikipedia)

One of twelve different versions of the station, this image gives the proof of the Impressionist love of the present day, modernity and its runaway sense of time. This steam powered engine will whisk you away from Paris in what must have seemed the blink of an eye. The hazy steam around it softens the iron and steel of its bulk and gives it a sense too that in a moment the train will have vanished, pulling out of the station to zip along to its next stop. No wonder it fascinated the Impressionists, with its vapor and quick movement measured in the instants they attempted to capture. Also, they happily hopped aboard those same trains for afternoons away in the countryside. In ways unthinkable before the train, the painters could day trip to the banks of the Marne or Argenteuil and the guinguettes and get back to their Paris garrets by bedtime.

Camille on her Deathbed, 1879

photo: RIbberlin (Wikipedia)

Not all however is steam engines with Monet. His 32 year old beloved lies here on her death bed, buried, according to custom for young wives, in her bridal veil. But as if he cannot help himself, in order to process the loss that is overwhelming him, Monet takes to his paintbrushes, once again to reflect on transience, now of youth and beauty, and of life itself.

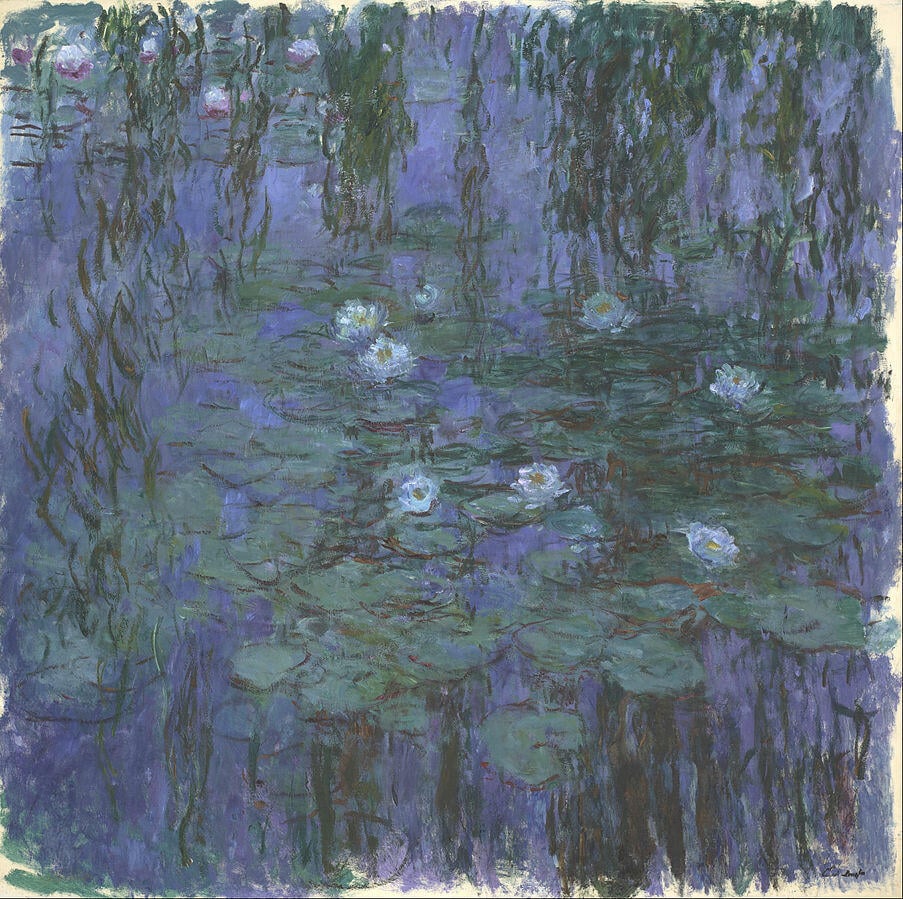

Waterlilies, 1916-1919

photo: Dcoetzeebot (Wikipedia)

Dating to the tail end of the Musée d’Orsay’s scope, in this particular example Monet’s beloved waterlilies are as ephemeral in their way as any of the above. They will obsess his painter’s eye, an eye itself suffering the effects of time with cataracts clouding his sight. As though sharing that optical defect with us, the flowers seem to disintegrate before our very eyes, disintegrating along with it the tradition of a subject in painting. Some voices say that this is the beginning of 20th century abstract art.

Auguste Renoir Bal du Moulin de la Galette, 1876

photo: Coat of Many Colors

Much more a people person than Monet, Renoir has chosen to portray his artist and model friends up in Montmartre on a Sunday. The working class loved this kind of open air dance hall with its cheap wine and galettes (savory crêpes -try some while you’re here!) He also has done more than one version of this image, more a portrait of simple joy than of any specific person. With his typical joie-de-vivre and “simple” dabs of color and light, Renoir conveys the raucous atmosphere of that recent invention of a day off from work.

Berthe Morisot The Butterfly Hunt, before 1895

Manet’s sister-in-law, Morisot was a girl in the Impressionist Boy’s Club. As a proper lady of a certain class, she could not, like her brother by marriage, go prowling the city’s nightclubs, painting their low-life denizens. So she painted a much more restricted world of wealthy women, the wet petals of her brushstrokes veiling as much as unveiling her subjects. Yet within their charm lies a subtle critique of those social, limitations as the women seem isolated, faces often blurred out of individuality. Moreover, even positive reviews were but backhanded compliments to her gender, praising her female nervousness and hypersensitivity, leaving more “serious” attempts at imagination to male artists: “painting a universe like a gracious mobile surface infinitely nuanced. Only a woman has the right to rigorously practice the Impressionist system, she alone can limit her effort to the translation of impressions.”

photo: Alonso de Mendoza

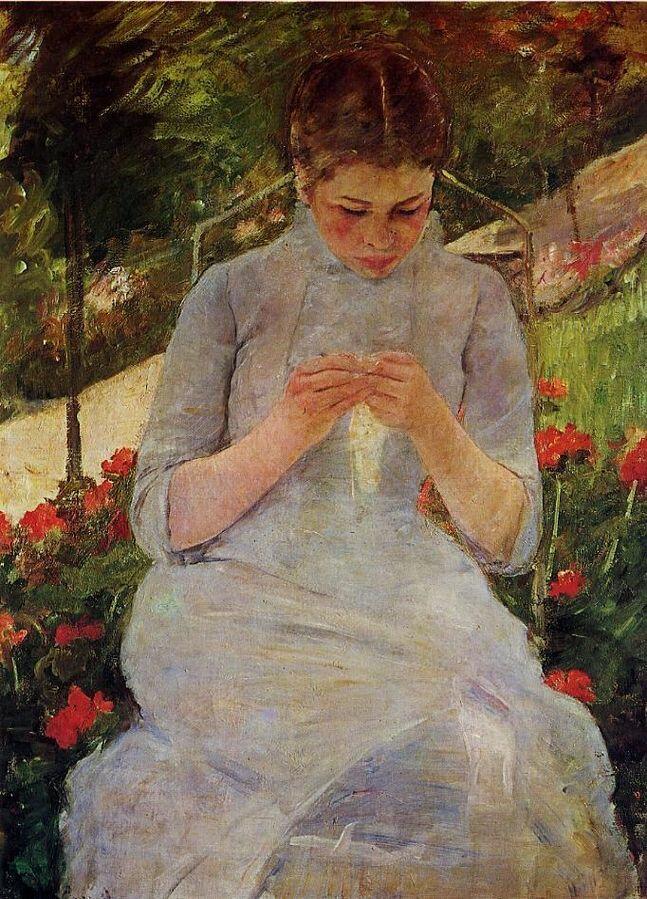

Mary Cassatt Girl in the Garden (also called Woman Sewing), 1880-1882

Cassat is the other woman Impressionist, one of the original Americans in Paris. Her father refused to pay for her art supplies. So fleeing the chauvinism of the post-Civil War US she made Paris her home where, like the upper-crust Morisot, Cassatt had her subject matter limited to the feminine sphere.

In an unusual exterior for Cassatt, here she portrays girl at her “work”, her sewing, concentrating in solitude of a garden. She could be a re-envisioning the medieval Virgin Enclosed, entirely modern in a simple young lady surrounded, as though protected, by greenery and flowers. This private moment also reminds us of Vermeer’s Lacemaker (see our Louvre blog entry, and tour), a portrait of a woman intent on her task, absolutely absorbed in the work before her.

photo: Acacia217

Gustave Caillebotte, The Floor Scrapers, 1875

photo: Dcoetzeebot (Wikipedia)

Another high-class toff like Manet and Dégas, for a long time Caillebotte was known more for collecting than his painting. Here we see just how wrong that was. The composition itself is intriguing, with, the angles and line of vision inspired byJapan’s fashionable woodcuts. But discreet social critique is within the choice as well. We must ask ourselves, who exactly is looking at these men on their hands and knees, hard at work in thankless labor. The viewer indeed looks not at them, not in the eye, but down on them and the sweat of their brow. Certainly the perspective is that of the owner of this clearly brand-new luxury Haussmanian apartment, with the means to afford the significant expense of having his floor planed and re-varnished when, as recent as it is, it cannot be in dire need.

The Post-Impressionists

Taken with the visual experiments of the Impressionist crowd, the artists of the following generation took their play of color, hue and light for their own sake. Less concentrated on the “here and now” of big city life, their work was more internal, even crossing over, later, into the dreamily symbolic.

Vincent Van Gogh

Perhaps the world’s most beloved painter, certainly the most famous of the Post-Impressionists, this genius worked through his notorious mental illness by way of his brush, creating beauty out of torment, a note of glorious hope in his bright colors defying the darkness that dogged him.

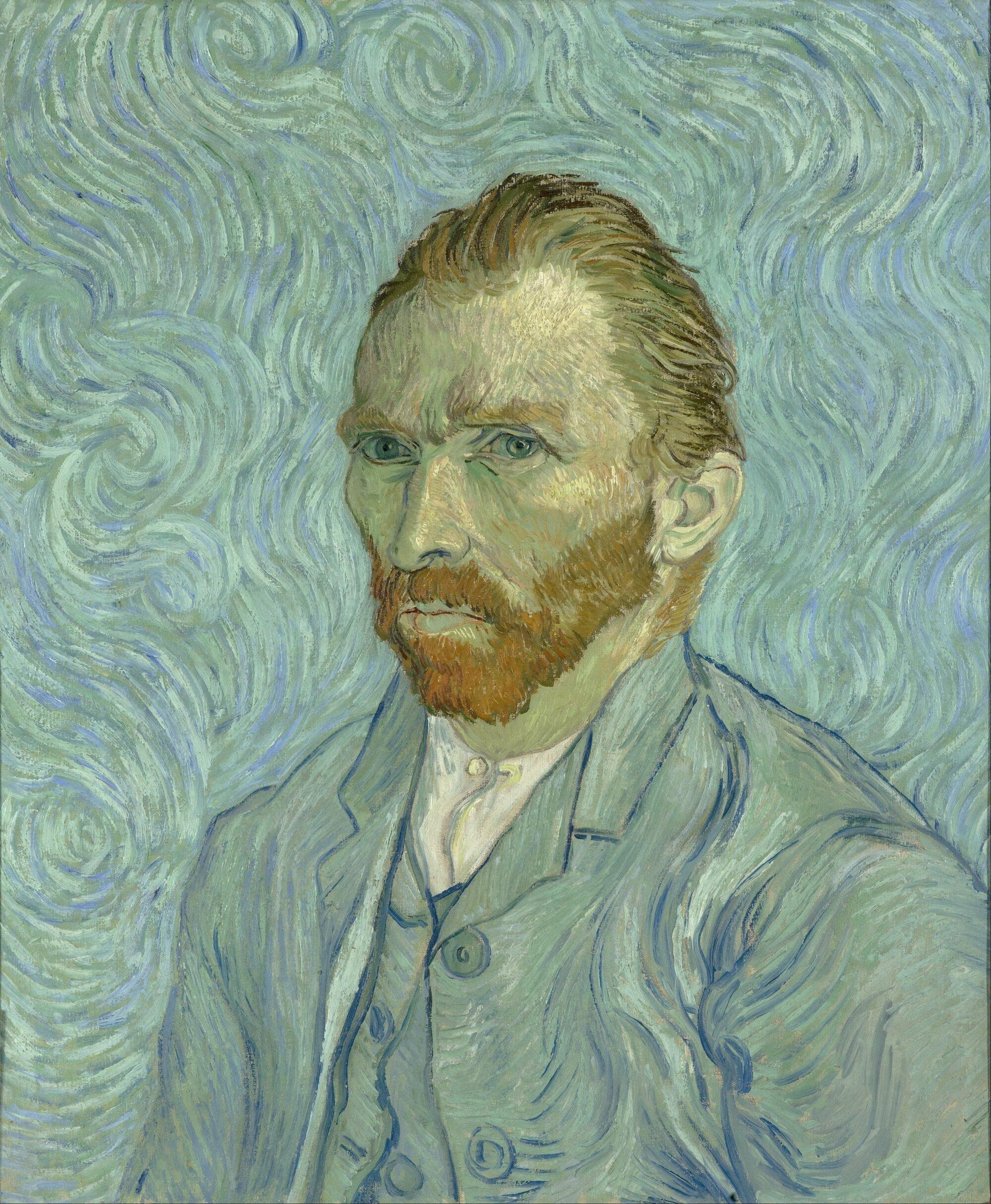

Self Portrait, 1889

photo: Dcoetzeebot (Wikipedia)

One of many, the artist painted this self-portrait before abandoning Provence where he had felt sure that, in Paul Gauguin’s company, he would find serenity and inspiration. Here, he wrote his brother, he hoped his features appeared more settled and at peace. Yet that hope is belied by agitated brushstrokes and haunted eyes, nearly a hallucination of upset; the artist delves into an introspection worthy of Rembrandt (see our Louvre tour). Unlike that other Dutch painter’s muddy colors, however, the pale tones of yellow and blue lighten even the turmoiled arabesques of this study in his own anguish.

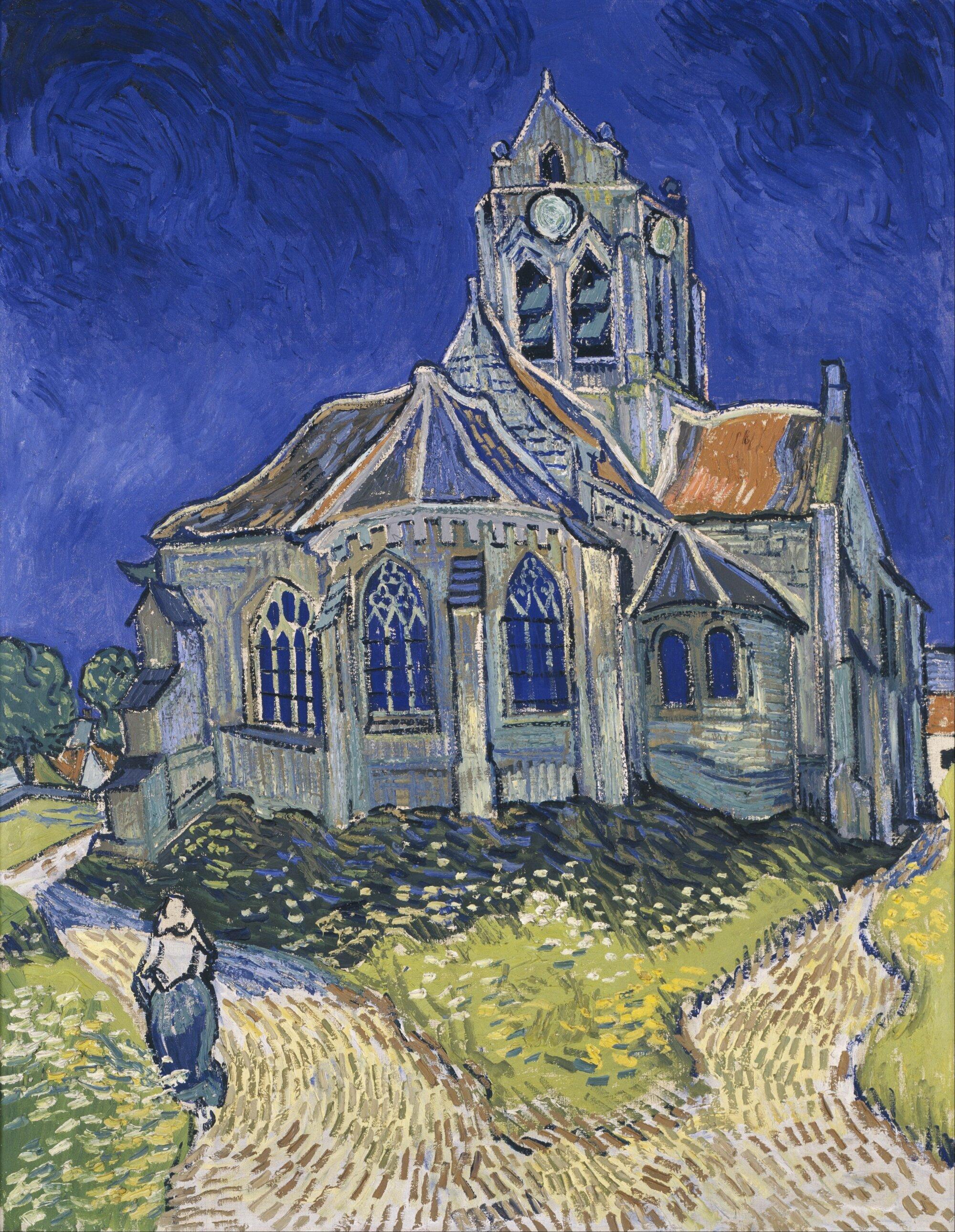

Church at Auvers-sur-Oise, 1890

Photo: DCoetzeebot

After Provence, Van Gogh ended his life outside of Paris in tiny Auvers-sur-Oise. Here he paints its church in the deep blue tones of medieval stained glass offset by the strokes of bright green. It is a haven before him, but note that he does not paint how the viewer, or he, might ever enter, despite the figure that has the secret. We have no access to its sanctuary.

Paul Gauguin The White Horse, 1898

photo: Dcoetzeebot (Wikipedia)

More green than white at all, Gauguin painted this horse out of the Tahitian hinterlands, among lilies and hibiscus as well as flowers with no basis in the real world but the painter’s imagination. Polynesian belief associated such creatures with the gods and the passage into the world after death. In this moment of pure enchantment, the horse definitely seems to us to be a symbol of something more, yet like the painter, we are but foreigners observing, confusedly, from the outside, a sacred moment whose meaning we can only guess at.

Gauguin frequented not only Van Gogh, but some lesser known painters called the Nabis, or prophets. Here are three of them not to miss at the Orsay.

Les Nabis

Maurice Denis

This painter also emanates a kind of sacredness as though he had his own personal religion and a feminine one, set in Paris– it's no surprise that he bought a priory to live in where you can see rotating exhibits of his work

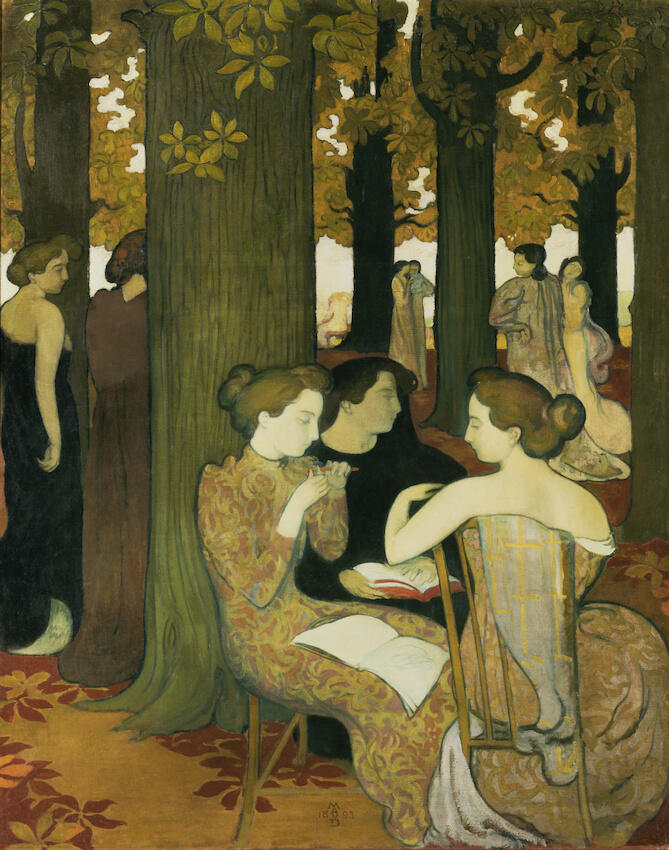

Les Muses 1893

photo: Thierry Caro (Wikipedia)

The nine muses, disguised as in present-day dress gowns and bustles, frequent some suburban Parisian haunt with its typical chestnut trees. It is autumn, the time of harvests, as we can see in the curves and counter curves of the leaves, trunks, and branches. But the harvest is also symbolic: this is a place of epiphanies where goddesses in modern guise commune with the sacred wood surrounding them, that is also just park, like any other in the city and its surroundings.

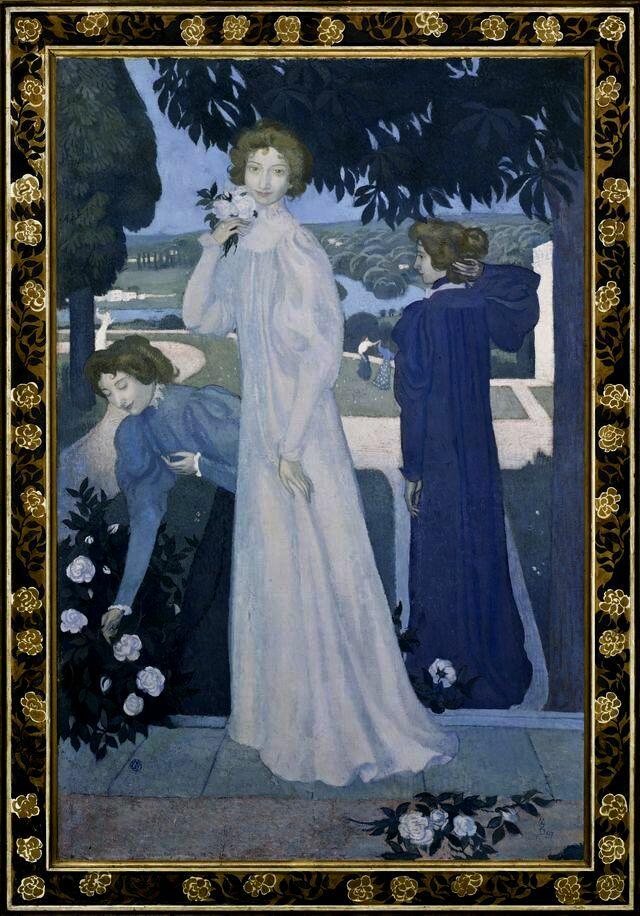

Portrait d’Yvonne Lerolle en trois aspects, 1897

photo: Pimbrils (Wikipedia)

Here, Denis has given us a kind of trinitarian goddess, or the Three Graces bound up in one sole woman. Nor is this the first time Denis will take this artistic tack in a woman’s portrait. One and many, she is an allegory unto herself, but it is to you, viewer, to decide of what precisely.

Felix Vallotton Le Ballon, 1899

photo: Dcoetzeebot (Wikipedia)

The flat space echoes the flat side-by-side colors, but they do not bore the eye as they might with a lesser painter. Instead the naively straightforward hues and intriguing planes make this child seem lost in a vast space as he chases his red ball in a park -- perhaps the Luxembourg Gardens -- likely feeling far indeed from tiny mother and nursemaid, in a personal adventure that might lead him who knows where, as Vallotton captures the immensity of the imagination of childhood and all its boundless possibilities.

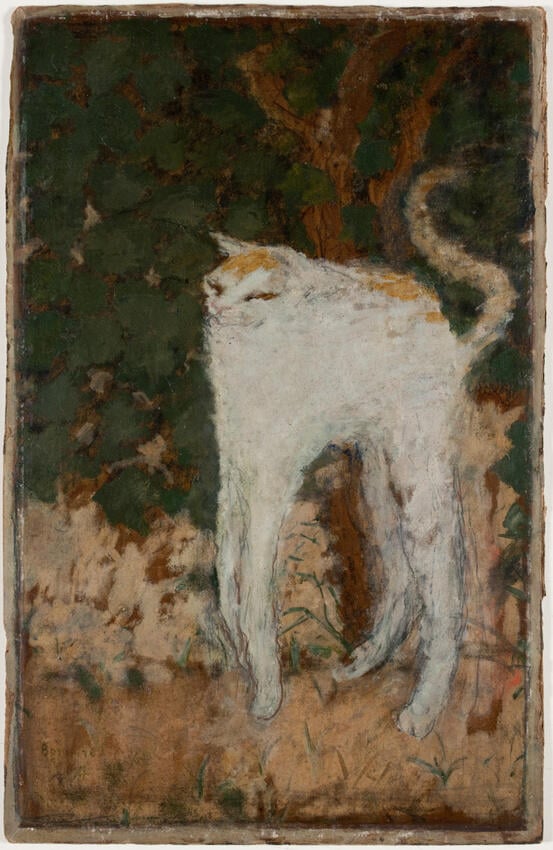

Pierre Bonnard Le Chat Blanc ,1894

photo: Thierry Caro (Wikipedia)

Bonnard’s own pet modeled for this comic little piece where a slow-blinking, back-hunching feline veers to the cartoonish. His bizarrely exaggerated long legs could not possibly carry him, but they echo the vertical of the canvas. Surely this is how tall the subject felt himself towering, on these impossible little nubs for paws. You can sense Japan again in both subject and treatment of this quintessence of cat. And you thought these tutelary deities of the internet were a present-day fascination!

Moving on from the Nabis....

Georges Seurat, Circus, 1891

photo: Coldcreation (Wikipedia)

The painter of Sunday in the Park with George fame, that pointillist masterpiece of a weekend afternoon on the Grande Jatte, took the lessons of the Impressionists in a different direction than what became the Symbolist movement. He was a more faithful heir in some ways, in his fascination with urban working class leisure. He is their heir in technique, too, taking their optical games of chromatic dabs further into what was baptized pointillisme. In pointillism, the viewer’s eye takes the artist’s tiny dots of mainly primary colors and reconstructs it into the scene portrayed. The Circus of 1891 is the last in a series of pieces on that same subject, giving an eerie stillness to the boisterous performance that you, as the viewer creating the scene by looking at, are actively participating in. As the final canvas Seurat was to paint before his death at 31, it is the closest thing we have to his artistic testament, the ultimate stage of development of the movement he created.

James McNeill Whistler Variations en violet et vert, 1871

photo: Maltaper (Wikipedia)

[at time of writing not currently on display], You might know him by his portrait of his mother, also here [at time of writing not currently on display], but spare some attention all the same for this American’s exquisite tonal interplay, with but the barest nod to figurative painting. All the pleasure of viewing it lies in the chromatic harmonies and brushstrokes. Later, concerning another of Whistler’s nearly-abstract pieces, one critic asked how an artist could demand 200 guineas for flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face. In the ensuing trial (no publicity is bad publicity in the modern world), the artist was awarded one farthing in damages.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

Red Head (The Bath), 1889

photo: Archaeodontosaurus (Wikipedia)

Probably posed in Toulouse-Lautrec’s Caulaincourt studio near Montmartre, by his favorite model, Carmen Gaudin with her signature red hair that the artist adored. This isn’t just a back, it’s someone’s back, a distinct individual, as opposed to Bouguereau’s standardized and general goddess of beauty. She is fragile, with her shoulder blades defined on her thin torso and the glimpse of a slender thigh, in the vulnerable moment of the bath. The painter has so angled your point of view on this frail personality, that you might have your eye at the keyhole here, an invasion of a private moment.

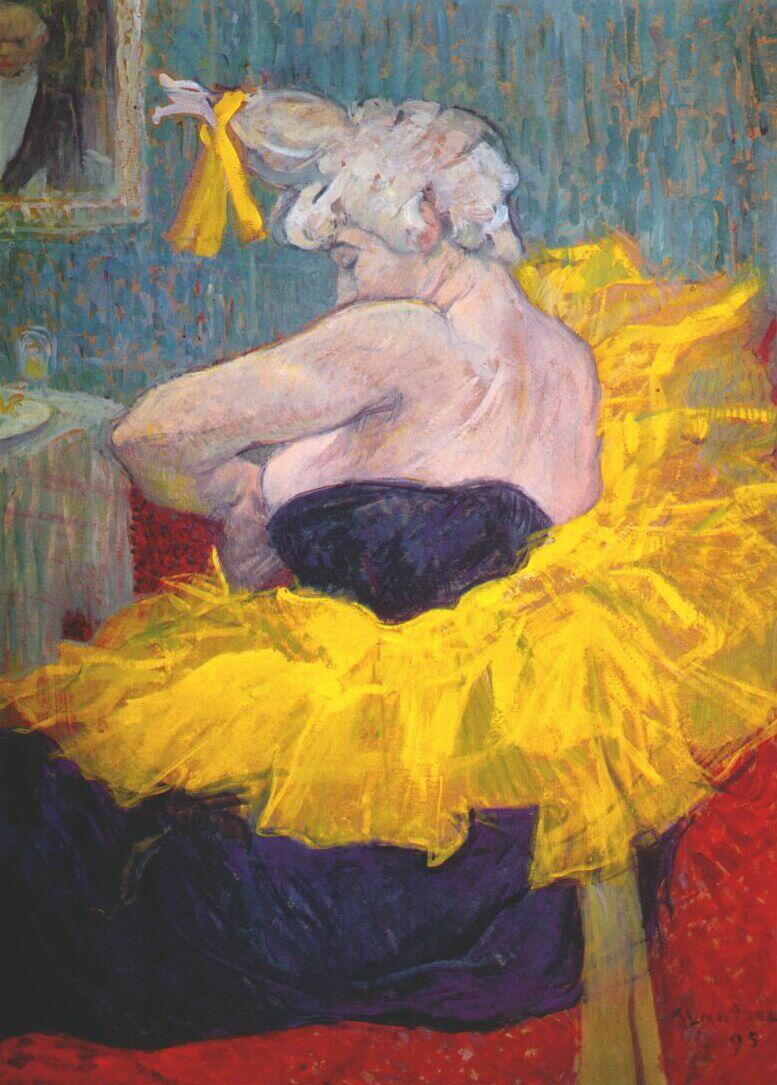

Clowness Cha-U-Kao, 1895

photo: Petrusbarbygere (Wikipedia)

Dancer and acrobat at the Moulin Rouge, her name combines chahut, a cancan kind of dance and the “chaos”, which would inevitably break out at her arrival on the stage. Who are we to witness her transformation via bright yellow tutu and white wig from woman into clown? Does the mirror hold the key? Looking closely we realize there’s someone in the dressing room with her to watch the metamorphosis. Is it you, the viewer? And what then is your relationship to Cha U Kao?

The much beloved Pre-Raphaelites are only a pale presence in the art of the Musée d’Orsay, but we do have:

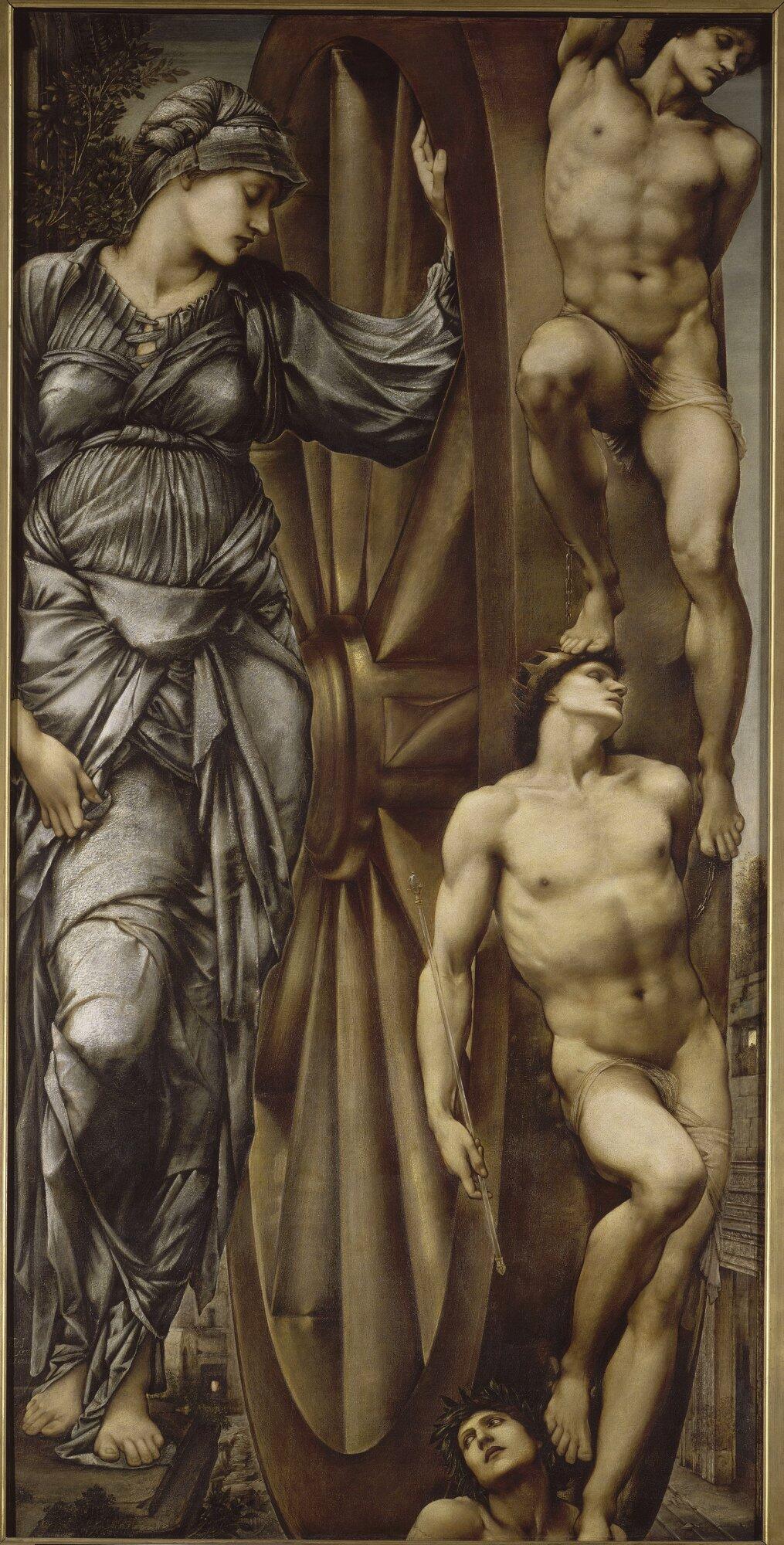

Edward Burne-Jones Wheel of Fortune, 1875 - 1883

The subject represents the perennial change in status and luck, ever turning, the wheel that both lifts

and crushes, the destiny of humankind. While this Brotherhood of English painters reveled in subjects

out of legends or figures from the Middle Ages, they generally did not paint medieval images

themselves. In contrast to the usual Pre-Raphaelite production, fortune’s wheel was a standby subject of

medieval artists. Here, one of Burne-Jones’ later pieces, the artist dives deep into his source of

inspiration to timelessly re-interpret one of its favorite themes.

photo: DimitryRozhkov (Wikipedia)

The Flowering Yellow Branch, 1901 [at time of writing not currently on display]

Strange genius of the pastel, Redon knew the Nabis well, but went further on the path of turning the subject into a simple excuse for playing pigment and pushing it to its furthest reaches.

photo: Musée d'Orsay

Redon once wrote he was portraying but “flowers of dreams, fauna of the imagination.” His works can’t, like the butterflies he often painted, be pinned down; they must fly free in the mind for any enjoyment. They are something elusive, all a play of color and light - that in itself is their meaning.

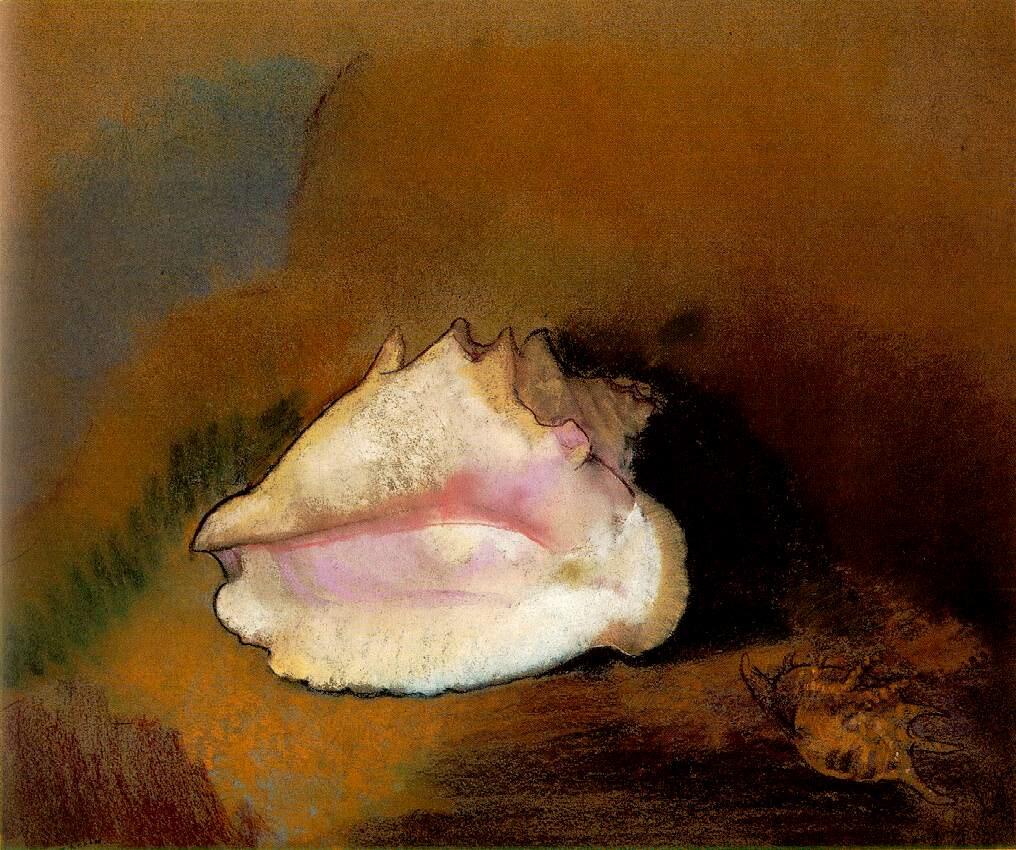

The Shell , 1912

photo: Cacaphony (Wikipedia)

It surges forth all pale, luminous shades of rose from its muted darker background. It might be waiting for Venus to come rising out of the tender pinks of the hollow. While the artist did paint that subject, here he makes no statement out of myth or literature. Simply a shell (or is it? Perhaps it does refer to birth after all?) that Redon teaches us to see anew in all its mystery and sublime blush.

That’s it for our introduction to the history of the Musée d’Orsay in its must-see art. If you like what you have read and want to see it for yourself and learn more, we can’t urge you enough to book a tour with us, skip the time-waste of the lines and get the full experience of the museum with a Memories France guide. We can’t wait to share our love and enthusiasm of this very special museum with you. Hope to see you soon!

Thank you!

Thank you so much for taking the time to read our blog! We are a small Paris-based tour guide company that prioritises a boutique personal experience where we can share our passion for our heritage and community with every individual that joins us. If you'd like to take a tour then head over to our website for an unforgettable trip to the city of lights. Also, check out our social media @memories.france for everything you could need to know for coming to Paris, from how to use the metro to coffee shops closest to each major monument, there is something for everyone!

Angelissa, Siobhan & the Memories France Family

If you're looking for more tips, itineraries, and insights into Paris, check out our social media!

Like what you see? Read our other blogs here!

- How to Use the Paris Metro: A Simple 6-Step Guide for First-Time VisitorsNervous about navigating the Paris Metro? Our practical, step-by-step guide covers everything you need to know — from buying tickets and reading the map to tips on avoiding common mistakes — so you can travel like a local with confidence.

- Can’t-Miss Summer Events in Paris 2025: Your Guide to What’s OnFrom music festivals and national celebrations to sun-soaked riverside fun, Paris truly comes alive in the summer. In this guide, we’ve rounded up the top events happening in Paris in 2025 — including Fête de la Musique, Bastille Day, the final stage of the Tour de France, and more — so you won’t miss a moment of the city's vibrant summer energy.

- 5 Best Châteaux to Visit Near Paris (within 90 minutes by train)Escape the city and explore royal estates, romantic retreats, and grand architecture—each less than 90 minutes from Paris by public transport. These five stunning châteaux are perfect for a memorable day trip into French history.

- Visiting the Iconic Notre-Dame Cathedral: What Not to Miss in ParisNotre-Dame Cathedral isn’t just a Paris landmark—she’s a symbol of the city’s history, heart, and resilience. In this post, discover her incredible story and get practical tips on how to visit, from what to look for to the best way to explore with a guide.

- Paris in a Day: The Perfect 1-Day Paris ItineraryRead here for our guide on how to spend one day in Paris. Showing you the major highlights, whilst still retaining that absorption of local culture, atmosphere and Parisian lifestyle that everyone comes here for!