It's Paris Fashion Week once again! Paris is home to high fashion, and to great, emblematic fashion houses, many of them showing here this week. We've decided to look back on two iconic figures in French fashion and their revolutionary takes on two dresses - Coco Chanel and the Little Black Dress, and Marie-Antoinette and her little white dress - and their impact at the time. Read on to find out more about two of the original fashionistas and get a lesson on the history of fashion in Paris!

Little Black Dress/ Little White Dress: Looking Back at the Paris' Fashion History from Chanel to Marie-Antoinette

You don’t usually think of the muslin frocks out of Jane Austen films and the iconic creations of the House of Chanel in the same breath but, perhaps, as we come up on Paris Fashion Week, we should spare a thought for two dress styles, and take a backward look what joins them across a century or more of of changing modes.

As Virginia Woolf famously said, "On or around December 1910, human character changed". She knew what she was talking about, writing in 1924, with the hindsight of the upheaval of World War I’s aftermath. It was on the precipice of this earthquake that Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel created the Little Black Dress, working on its prototypes as early as 1912. She drew on maid’s wear, with, under her white apron and cap, the serviceable dress of black, that you’ll recall from Downton Abbey’s costumes for the downstairs servants. That too, though less remarked upon, was not without a frisson of the naughty.

Yet there was more to it. Only two years later at that war’s 1914 beginning, she was also drawing on the mourning wear donned by the mothers, sisters, wives and fiancées who would eventually lose 1,4 million to the war - over ten percent of the nation’s young men. Class divisions crumbled in the void of the loss of life. This was also the event of the French flapper’s emergence, the garçonne, (more literally the ‘boy-girl’) with her short hems and shorter hair.

Figure 1: Chanel, LBD 1917-1919 Paris, Patrimoine de Chanel.

Furthermore, young single women had entered into the fray of activity. With the men gone, this new woman had to work, both to earn her living and keep the country functioning. She stayed on in her job after the end of the war in 1918, since the men simply did not come back or came back incapacitated. And new kinds of jobs galore were springing up that we would eventually call “pink collar” the telegraph workers, the shopgirls, and phone operators and more.

The New Woman clamored for simpler dress, distinct from the over the top luxurious creations of the Haute Couture world of before, the gowns in their heavy, rich velvets and bright silks, with their highly structured undergarments, corsets, and layers and layers of petticoats. This was pre-war style, the kind of custom made fashion cut for the grandes dames by the likes of the House of Worth.

Figure 2: House of Worth, 1900, New York City, The Met Museum

But the shop girls and phone operators wanted something else, something they could move in and be as chic as the great ladies of high society. Coco Chanel heard them and in 1926, gave the Little Black Dress, or LBD as it became known on its official runway début. Chanel said she wanted to create a look of deluxe poverty, and a simpler silhouette of a sheath dress, a kind of column look, a new kind of uniform that a woman could wear anywhere and retain an air of minimalist elegance. Her own griffe would cost, but there could be affordable knockoffs.

Figure 3: Chanel, LBD, 1927, New York City, The Met Museum.

But for her own clientèle, she singlehandedly brought about a new vogue for people who liked to declare in the clothes they wore, that they simply didn’t care about fashion, although they very much did. Pretending to be above it all, therefore, in the paradox that la mode often is, they affirmed their superiority over those “still” running after the latest trends. Thus they discreetly embraced a sort of social superiority in a world in which doing so overtly was now frowned upon.

She knew her game, did Coco Chanel, since a de rigueur element to any capsule wardrobe remains even today the LBD, over a century after she first worked its prototype.

What indeed could Chanel’s masterpiece have to do with an early 1800s frock flick’s virginal muslin tunics, what we might call the Little White Dress?

Figure 4: US or European 1810-1812 New York City, The Met Museum.

One version – for there are many story arcs to its rise to fashion supremacy – goes like this:

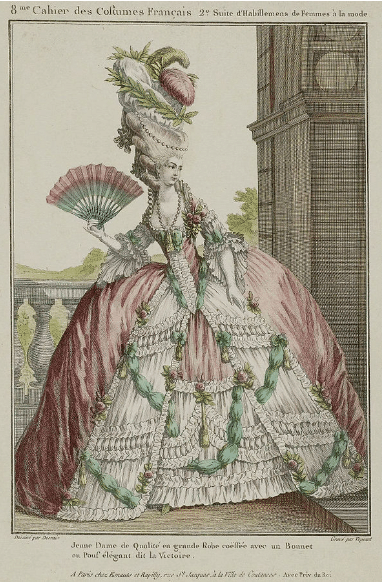

In France, at least, the grandmother of the style came about in Marie-Antoinette’s own reaction to her vast hoops and big-hair hoopla. Everyone knew her wardrobe cost a king’s ransom and it did not contribute to the popularity of a daughter of the House of Austria, France’s traditional enemy. She failed to read the room. So changing tacks, after a vast many rumors and personal attacks, she thought then to play it simple. Her personal fashion designer, Rose Bertin, had a gown made for her from cotton muslin. A freely formed, breathy bit of whimsy, falling to the ground without the panniers’s fake hip width, the stiffly embroidered stomachers, and the princely dyes out of a rococo palette dream.

Figure 5: Cahiers des Costumes Français 8th volume, 2d suite, 1778, London, Victoria and Albert Museum.

It hearkened back to some idyll of a misty past, something out of Rousseau’s idealistic imagination, who thought that the trappings of fashion denatured us and brought about the kind of social hierarchy that the French Revolution hoped to bring down with the Bastille.

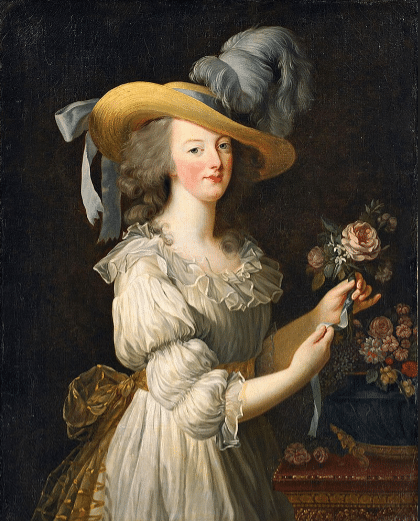

But this is 1781, eight years before that fateful day, and the young and lovely queen of France has given to casting off the stiff royal etiquette, as well as the silks and velvets equally weighing her down, with their assortedly structured underpinnings, or at least in her Versailles getaways of the Petit Trianon and her play-dairy of the Hamlet. And certainly as early as 1783, at Marly with her long awaited pregnancy. For the dress, a chemise or shift as we would call it, resembled nothing more than her underwear.

Figure 6: Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun, Portrait of Marie Antoinette en Gaulle, 1783, Château de Versailles, photo: ~riley, Wikipedia

Enter the queen’s portraitist in title, the charming Elisabeth Vigée Lebrun, who painted the queen in precisely this kind of negligée, “undress” in her official royal image thus arrayed in for the salon of that same year. They both hoped that this would signal a “simple” queen, at heart one of the people, and not caught up in the courtly intrigues the pamphlets accused her of, as though she had just stepped out of a peasant idyll, a shepherdess monarch. Yet when this portrait was shown on the walls of the 1783 Salon, it outraged people as though the Queen of France were sporting around in her skivvies, as though to thumb her nose at the populace. She couldn’t win.

Young women across Europe and beyond picked up on this vogue of artistic reform, and soon these dresses held sway over Western tastes, a fashion that started as a kind of artsy antifashion, drawing on Rousseau’s penchant for equality between men (if not of women) and really coming into its own in the aftermath of another great war with mass death, the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars that followed.

This too led to a superficial restructuring of society, levelling class structures that previously seemed written in stone, a time of upheaval and mourning. For even if Napoleon reinstated the aristocracy, he also created scads more of his own titled nobles in what he imagined would bring about a meritocracy.

So in fact, the anti-fashion element, the rebellion element, as well as that vision of equality that they embodied bring together these two types of dress, sheaths that refuse color, in their simplified columnar minimal, style democratizing dress in the aftermath of wars and their casualties.

Moreover, in rejecting the bright spectrum of rich color that came before, the aesthetic’s transparencies of the finest lawn over simple fleshcolored petticoats and short stays rather than fully boned corsets also had an erotic thrill to them that scandalized at least as much at the social implications of a dress of equality.

Perhaps we’re seeing now that though black and white, these dresses, a simple, colorless sheath, coming out of a time of mass death and the levelling of ranks, have far more in common than we might have thought at first glance.

Fashion has long been dismissed as a frivolous pursuit, but in looking longer, in time as well as depth, it can say some truly profound things about the world we live in and that which we aspire to.

If you'd like to learn more about the life of Marie-Antoinette, and see her gorgeous private mansion and gardens of the Petit Trianon hidden away at Versailles (as well as the infamous portrait above), we'd love you to join us on our tour!

Thank you!

Thank you so much for taking the time to read our blog! We are a small Paris-based tour guide company that prioritises a boutique personal experience where we can share our passion for our heritage and community with every individual that joins us. If you'd like to take a tour then head over to our website for an unforgettable trip to the city of lights. Also, check out our social media @memories.france for everything you could need to know for coming to Paris, from how to use the metro to coffee shops closest to each major monument, there is something for everyone!

Angelissa, Siobhan & the Memories France Family

If you're looking for more tips, itineraries, and insights into Paris, check out our social media!

Like what you see? Read our other blogs here!

- How to Use the Paris Metro: A Simple 6-Step Guide for First-Time VisitorsNervous about navigating the Paris Metro? Our practical, step-by-step guide covers everything you need to know — from buying tickets and reading the map to tips on avoiding common mistakes — so you can travel like a local with confidence.

- Can’t-Miss Summer Events in Paris 2025: Your Guide to What’s OnFrom music festivals and national celebrations to sun-soaked riverside fun, Paris truly comes alive in the summer. In this guide, we’ve rounded up the top events happening in Paris in 2025 — including Fête de la Musique, Bastille Day, the final stage of the Tour de France, and more — so you won’t miss a moment of the city's vibrant summer energy.

- 5 Best Châteaux to Visit Near Paris (within 90 minutes by train)Escape the city and explore royal estates, romantic retreats, and grand architecture—each less than 90 minutes from Paris by public transport. These five stunning châteaux are perfect for a memorable day trip into French history.

- Visiting the Iconic Notre-Dame Cathedral: What Not to Miss in ParisNotre-Dame Cathedral isn’t just a Paris landmark—she’s a symbol of the city’s history, heart, and resilience. In this post, discover her incredible story and get practical tips on how to visit, from what to look for to the best way to explore with a guide.

- Paris in a Day: The Perfect 1-Day Paris ItineraryRead here for our guide on how to spend one day in Paris. Showing you the major highlights, whilst still retaining that absorption of local culture, atmosphere and Parisian lifestyle that everyone comes here for!