This week Paris Fashion Week Spring-Summer 2026. With the whirl of Fashion Week upon us once more, let us take the time to combine two of our favorite things, la mode and Impressionist painting! You may not immediately associate Monet and Renoir with haute couture, but the movement they led was in love with up-to-the-minute clothing trends.

It all happened against the New Paris backdrop of the mid nineteenth century, the Impressionists’ natural habitat. During the Second Empire, Napoleon III’s prefect Baron Haussmann began to overhaul the crabbed and cramped medieval-style city into the wide, tree-lined boulevards we know and love today. By 1870, the transformation was pretty much complete and had created a brand new urban lifestyle to go along with it. This is what the Impressionists –whose first show was in 1874– wanted to paint: something resolutely modern. Those artists wanted to catch the blink-and-you’ll-miss-it moments of what has been called the “Capital of the Nineteenth Century.” Whether in its greener suburbs or in the midst of the hustle and bustle of the city center, their work recorded the ever-evolving ephemera of fashion as integral to their attempt to butterfly-pin the changing light and transitory flashes of glimmer and glint in plein-air painting.

How did fashion work, though, in those days?

The Mill of La Mode

- At the pinnacle stood the trendsetters, such as the reigning consort, the Emperor’s Spanish wife Eugenie de Montijo and her inner circle. She was granted 100,000 francs a year for her wardrobe. While this may seem excessive – well, it is. Yet at the same time, there was a reason: customs of the court demanded a woman dress and redress for each stage of the day. A different gown was appropriate for morning, afternoon, and evening, with specific codes for each, whether that be indoor or outdoor, a receiving or a visiting dress. Records show the Empress packing twenty for one sole week at their country château in nearby Compiègne. The image below gives you a taste of what that looked like.

Waiting, Château de Compiègne, 1855 (credit: Wikipedia, LordT)

- Right about the time it was painted, the cage crinoline came along, giving the expansive ruffles we see here. While a wide skirt had been in favor for some time at that point, this light whalebone contraption replaced layers and layers of stiff and heavy petticoat, allowing for more freedom of movement while exaggerating its bell form to an outrageous circumference. At the same time, the hoops also recalled the panniers of Marie-Antoinette’s generation. Since the Second Empire began in a coup, suggesting a continuity with the last reigning royal family was a bid for a legitimacy. The sky-high price for Eugénie’s wardrobe must have seemed like a fair one to pay.

- On the heels of whatever whim of Eugénie and her crowd, the upwardly mobile would hop on the trend and spend their disposable cash on imitating it, in an effort to blur the lines separating grande bourgeoisie from the true “happy few.” In a world where the ladies of this class did not work (at least not paid work), this conspicuous consumption was funded by father or husband. As with the Empress, this also must have seemed a fair price to the gentlemen in question, as it became a display of male purchasing power, as read through how their wives and daughters dressed.

- For those with more ambition than funds, there was the new phenomenon of the department store, like the 1850 revamp of the Bon Marché into a form close to what we know now (Ah, Paris! Where retail therapy is a time-honored cultural and historical custom!). These institutions even had bargain, ready-to-wear versions of high fashion. This petite bourgeoisie imitated those socially above them with pre-made articles that were a passable, if budget, option for those who likely worked for a living and did not necessarily have a family that could afford the luxuries of a dressmaker.

- The ranks of milliners, laundresses, and other “working girls” (sex work in this era was often less a dedicated profession than shop girls needing to meet end-of-the-month bills, then going back to selling hats until rent was due again), who did not often have such generous mates, would imitate the middle classes with their own touch. The dresses may have been cheaply made, but since these women were themselves often in the garment trade, they could possess a flair that the upper crust might envy, setting their own trends.

- Meanwhile the elites would again need to distinguish themselves from the unwashed masses, affirming their in-crowd status by adjusting hoops to bustles, along with sleeve-shapes and necklines, and the cycle would begin again, voilà

The Impressionist Catwalk

Armed with that knowledge, let's now take a virtual stroll through the Musée d’Orsay and see what la mode meant in those palmy days and how it was painted by the Impressionists and their friends in those brilliantly colored collections.

James Tissot (1836-1902)

Miss L.L. (Portrait of Mademoiselle L.L.) 1864 (not currently displayed)

(credit : Wikipedia:, Nono314)

Impressionist-adjacent painter James Tissot shared the movement’s interest in the modern world, using fashion as a way to express that interest in the here-and-now. Son to a milliner and a drapery merchant, he came by the interest honestly. We can see it in this modish and mysterious Miss L.L., whose identity is lost to time. But by 1864, tastes among those rich enough to indulge the change were moving to a slightly narrower skirt silhouette. It’s perceptible here, if we compare this young woman to Eugénie and her ladies. To emphasize Ms L.L. 's status, Tissot has arrayed her according to the recent shift. Moreover, he clothes her in the Spanish style, a vogue winking at the Iberian origin of the Empress, with her 100,000 franc clothing budget. Mademoiselle even sports a typical black and red color scheme in keeping with the same, along with her bolero jacket. It highlights either her belonging to that enviable circle or her desire to seem to.

Claude Monet (1840-1926)

Luncheon on the Grass (Déjeûner sur l’Herbe ), 1865-1866

(credit: Wikipedia, Alonso de Mendoza)

We seem to be in a countryside setting, but we are actually not far out of the city limits, near Fontainebleau, which is 35 miles south of the capital, all a poor painter could afford if he was actually paying for it (he didn’t always). Yet even if this seems bucolic, it’s that ultimate invention of modernity, the train, that in 1849 rendered Chailly-en-Biére, a nature reserve since 1862, accessible. Three years later Monet and his beloved Camille, modeling here, spent the summer at Chailly, so that he might paint this masterpiece, cutting costs further by using friends to pose and catch the lovely seasonal light. In fact his studio roommate is Frédéric Bazille in the right foreground. The pals are dressed for picnicking, in informal comfy jackets. The women, however, are in fine array and pose as if they were magazine models showing off their duds. Or rather, they are posed. Monet, like a Tim Walker of yore, has placed them in studied attitudes, the better to show off the finery he has dressed them in, far above their station. Camille stars, front-and-center in a gorgeous gown of the best polka dot muslin, with all the most stylish details. It’s as if he wants to dress her in all the accoutrements that only his imagination could afford, and his painting career at this stage could not. The gown picks up the late-afternoon light, like a manifesto of what the whole Impressionist agenda will be, hearkening to the fleeting pleasures of a day in the country, in the later afternoon, just when duty calls and we must return to urban life.

Women in the Garden (Femmes au Jardin) 1866

(credit: Wikipedia,The Yorck Project (2002) 10.000 Meisterwerke der Malerei)

In a sister-painting to the Déjeûner, Monet’s Women in the Garden clearly winks at the portrait of the Empress and her ladies-in-waiting, all crinoline and pretty hues of flounce and frill. In a further nod to Eugénie and her Spanish origins is the star of this idyllic show, in a “señorita” style jacket. That woman is Camille, again, ….as is the woman in peach with the bouquet... as well as her companion in profile to the left, like a photo-montage straight off the pages of Vogue. It’s as if Monet could not decide which gown most suited his beloved model, so he simply paints her thrice over. Or perhaps he could not pay more models than just her and the redhead picking the flower? In his early days, “Dine-and-Dash” Monet mooched off friends, leaving a trail of bills behind him wherever he went. But in his mind and with his mind’s eye he could clothe his companion in the finest muslins and silks, with cutting edge detailing – note seated Camille’s extensive and finely wrought soutache -- like grand ladies of the highest social rungs. In so doing he could also explore how different fabrics bounce or absorb light, an Impressionist hallmark. In these paintings, Camille becomes a kind of paper doll that Claude arrays in the latest of Parisian luxury, acting in some sense as her couturier, and again posing like an early fashion photographer. In fact the garden setting is also a reference to current fashion plates which so often ensconce the engraved female figures amongst greenery, either gardens or potted palms.

The painting got snatched up by his immediately by his studio mate Bazille whom we saw in the Déjeuner sur l'Herbe.

Frédéric Bazille (1841-1870

Family Reunion (Réunion de Famille) 1867

(credit: Wikipedia, Shonagon)

At the age of 29, Bazille fell in the Franco-Prussian War, four years before the first Impressionist exhibition in 1874. Because of his premature death, his is not the household name that Monet and Renoir are. Yet Bazille and Monet rented a studio together in Paris at the time, and belonged to the Atelier Gleyre along with Sisley and Renoir. By the time of this paintin, Bazille was under the spell of what would become the Impressionist pursuit of the play of light on textured textiles in an open-air setting. In this Family Reunion, just like Monet was nodding to Winterhalter, Bazille was nodding to Monet. You can tell he owned (and loved!) the Women in the Garden. Painted three years before his death, this Réunion gives us an image of his family gathered under a chestnut tree at their country property near Montpellier in Southern France. While Bazille’s love of the light of his homeland is immediately palpable -- and typically Impressionist-- we can also see how interested he was in clothing and how it defined a social role. The hats on some of them tell us they have come from outside the home, and are therefore visitors, which an 1860s viewer would also know by their heavier fabrics and more muted colors. The light cotton dresses of the Bazille daughters are perfect for receiving guests in the home but such flimsy and fragile fabrics would not be appropriate for going out. Their mother reigns over the scene to the left in a gorgeous blue next to his father. The gentlemen’s shoes are all buffed to a bright shine, despite their treading the dusty summer ground. As for the rest, the men wear much drabber colors than the ladies, nor are they as highly individualized- in fact they tend to look alike. In a bourgeois family like this, the ladies’ array signals the wealth of the men that pay for it, as in investment in showing off to the world social status and income. It’s worth noting, too, that everyone is looking toward the viewer (note the painter Frédéric, who painted his own figure in back left much later), except for one person. Bazille’s father was not best pleased that his son his given up the respectable study of medecin to become a no-account painter, and is in fact, to add insult to injury, painting him now.

Return to Monet

Mme. Louis Joachim Gaudibert,1868

(credit: Wikipedia, The Yorck Project (2002) 10.000 Meisterwerke der Malerei)

Let’s go back now to Bazille’s more famous studio-mate. Monet was never much of a portrait painter but then rich merchant Louis Joachim Gaudibert asked him to paint his wife, Marguerite-Eugénie-Mathilde. Church mouse poor, the artist was in no position to refuse. But he went at the project with his usual originality. Instead of a study of her face, Monet has her turn her head turned away; we’re left mainly with a dress to admire rather than a woman, a silk afternoon dress to be specific. The modest hue of brownish beige marks her for a respectable married woman. Gone not only are the bright, fair colors of the Déjeûner and the Garden’s younger, unmarried set, but also their crinoline hoops, now passé. The silhouette is weighted more to the back, and Madame’s hem trails the floor of her parlor, where she’s be ready to receive at-home guests. Of course to move about, she’d need to have that train looped up, but this is not a walking dress. Happily, chez les Gaudibert there are servants to usher guests into the parlor and serve the tea.

Edouard Manet (1832-1883)

The Balcony (Le Balcon)1869

Part of the vogue for all things Spanish, this painting refers to Goya’s Majas at a Balcony, (1808-1814), a compliment to the Empress’s homeland.

(credit: Wikipedia, Escarlati)

To the left of the French painting is Manet’s friend and muse, who in five short years will become his sister-in-law, the Impressionist artist in her own right, Berthe Morisot. He clothes her and her companion in the triangle skirted silhouettes of society ladies on the eve of 1870. Putting her in the role of one of Goya’s majas, he emphasizes how she is closed off from the world. Is she sheltered? Or imprisoned? With her intense gaze outward, she seems to be wishing she were anywhere else, perhaps longing to go out among the throng, on one of the new boulevards below the balcony, into the hubub and life as it is lived. Manet has very carefully chosen her costume, however, for she wears an at-home dress for receiving, and as an upper class lady, she will only leave the home under strictly supervised conditions. You can imagine him patting her pleats and arranging her sleeve just so, like any perfectionist shutterbug of the fashion world meant to convey his vision and meaning.

Auguste Renoir 1841-1919

Dance at the Moulin de la Galette (Bal du Moulin de la Galette) 1876

(credit: Wikipedia, Coat of Many Colors)

Montmartre! The very name evokes artists and their models, a bohemian paradise bursting with genius and joy! Outside the Parisian city limits, wine was cheaper here, just like the rents, and so it became the haven of those with more talent than money, but also other people scraping together some kind of living. For the women that meant laundresses and hatshop girls, milliners and their assistants. One of the quarter’s most popular rendez-vous was The Moulin de la Galette. Refreshments were priced to please, and – as an outdoor café with dances held Sundays in summer – what’s not to love for a starving artist? Girls, light, color, and movement all there for the painting. Renoir was a regular among this crowd, all looking to spend a few sous in their limited free time. This is where he also scouted for models, among the pretty customers (entry was free for women), such as the very seamstresses who sewed for the wealthy, just like Mimi, the ill-fated heroine of La Bohème -- and then went and created their own fashions from the scraps, completing the cycle of the Mill of la Mode we spoke of above.

The Swing (Le Balançoire) 1876

(credit: Wikipedia, Themadchopper )

Renoir then proceeded to paint Jeanne Samary whom he encountered at the Moulin (her sister Estelle is in the blue and pink stripes of the preceding painting). The nearby rue Cortot offered a cottage with a sizeable garden that he could use as setting (that you can still visit today in the Musée de Montmartre). Jeanne wears a dress made of princess seams that skims the body’s line. Crinolines and hoops, even the bustle, have all vanished: grand couturier Charles Frederick Worth swept them away like so many relics of a bygone era. Now a sheath dress shows off curves. While there maybe swags and flounces, they highlight an unbroken line for a “long limbed” silhouette. Real princesses, such as Alexandra of Wales, for whom the cut is named, had them custom tailored. A lass of the working class, however, would have had to be satisfied with a department store knockoff -- or indeed the work of her own hands -- had she that much leisure. But, for Renoir, Jeanne the real princess in a cheap but charming frock, all buttons and bows underlining the fashionable vertical line and enchanting her straw-hatted suitors

Gustave Caillebotte (1848-1894)

Boating Party (Partie de bateau), 1877-1878 (not currently displayed)

(credit: Wikipedia, Versailles39)

At the other end of the social spectrum, Gustave Caillebotte was, like his friend Manet, and Degas too, an upperclass man-about-town, and collector of the Impressionists’ work, while a painter himself. Here he shows us a close-up of a gentleman rowing an unseen companion on the Yerres near the painter’s family country house. The pastime was a new one among that set, one of the few instances a gentleman could be seen in his shirtsleeves (it wouldn’t do to rip a seam tailored precisely to one’s shoulders). Yet he still sports the vest of his suit and a top hat in these circumstances, while his bowtie is perfectly knotted, even as he breaks a sweat in his efforts with the oars. This perfectly proper dandy is a far cry indeed from Jeanne’s humble beaux above.

Edgar Degas (1834-1917)

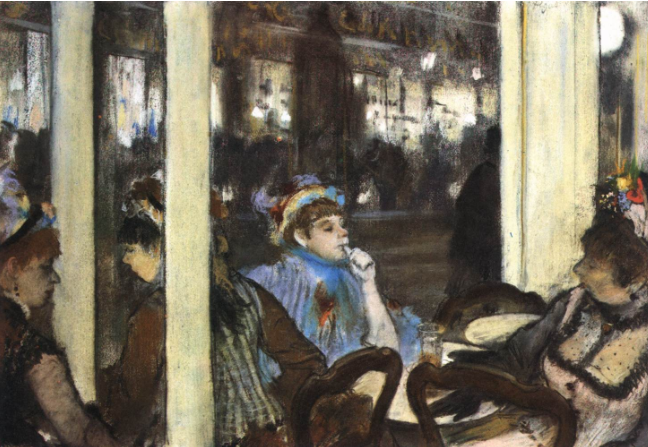

Women on a Café Terrace, Evening (Femmes devant un café, le soir) 1877 (not currently displayed)

(credit: Web Gallery of Art)

Haussmann’s broad avenues meant space for eating and entertainment establishments which had room to spread out on the new, ample sidewalks. Here any passerby might sit for a moment, or an hour, or an evening and rest with a coffee or glass of wine, simply watching the of the City of Light go by. It’s certainly a feeling any visitor to Paris might sympathize with, whatever the century. And they did, as early as those flocking here with the 1867 Expo, enjoying the spectacle of Paris. The following decades cemented this social phenomenon into an institution which survives heartily – and happily -- to this day.

Yet there were other kinds of “fauna” drawn to these places. An unaccompanied lady might dare sit there, but if she did so in certain cafés, a man would not be long in approaching her, especially depending on how he read her dress. Here Degas shows us women that would be correctly read by such a man as available by the hour - loud dresses, badly fitting, glaring and bold. Like the more refined apparel of the proper women belonging to the world of Manet or Bazille or Caillebotte, this too was a display meant for men. These men, however, are not fathers and husbands showing off their wealth, but potential clients prowling around for a good time with company that comes at a price. This two women appear to be resting between customers, complaining to each other with a thumb bite that says “I got peanuts!”

Oddly enough, Impressionist women are far less concerned with the sartorial details than the men!

Berthe Morisot (1841-1895)

Manet’s muse and sister-in-law came from the same social class that allowed the older painter to slum nightclubs with ready cash. Morisot, though, by necessity led a more restricted life appropriate to a bourgeoise. Her subject matter turned to young women in daily activities of the upper-classes, but her role as a woman and her close relationships to those modeling for her meant that she had a private access that Manet, for all his money and masculine independence, did not. Manet liked to paint nudes like Olympia, and could afford their rates, but the different stages of a women’s toilette was something that men could only know from the outside looking in, not as Morisot knew it from living it, participating in it, regularly, through her own experience, or that of her sisters or mother or others. “Respectable” women in fact were taught to keep these matters from their husbands.

Jeune femme se poudrant, 1877

(credit: Wikipedia, Thierry Caro)

Here we see a young woman in her underpinnings powdering her face, something Morisot would have done or seen done a million times, and yet the whole act is caught up in the blur of her brushstrokes – we don’t see details, as if the haze of the powder is obscuring the particulars lace and seam.

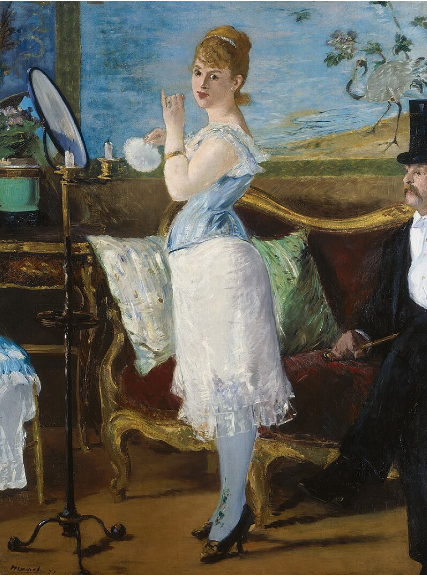

Manet did paint a similar scene (just who inspired whom here?) the very same year.

But this, unlike Morisot’s scene, is no “lady.” We see her parading her preparations in front of her “patron” (the grand courtesans of this class did not have “clients” but rather “patrons”) dreaming of her enjoying her charms.

Edouard Manet, Nana, Kunsthalle, Hamburg, 1876 (credit: Wikipedia, Veriditas)

Unlike Morisot, Manet describes in great detail the corset’s boning, the clocking on the stockings, as though he asserting bragging rights on such privileged knowledge, even if it is a “public” woman. Morisot, on the other hand, preserves the privacy and the intimacy of a moment only she has access to.

Young Woman in a Ball Gown (Jeune Femme en Toilette de Bal) 1879

(credit: Wikipedia, Dcoetzeebot)

Even in a work titled for the gown the young lady is wearing, her dress’s details are but a blur of pale color for. In fact, although Morisot (and her model) are residents of the capital, it’s the artist’s painting style, rather than her model’s finery, that is described by one period critic as possessing that Parisian chic,in this perfect summary of the Parisienne’s mythos:

“Mme Berthe Morisot is French through the distinction, elegance, gaiety, and insouciance. She loves painting the stirring, the joyful, the cheering. She grinds flower petals on her palette, to strew them over the canvas in spirited, breathy touches, scattered more or less by chance, which harmonize and combine to end up producing something refined, lively and charming.”

Mary Cassatt (1844 -1926)

One of the New Woman crowd, Mary Cassatt left her Philadelphia home and her overbearing father to study art in the just-as-new Paris, where she met up with the Impressionist crowd and never looked back.

Girl in the Garden also called Woman Sewing (Jeune fille au jardin ou Femme cousant), 1882

(credit: Wikipedia, Dcoetzeebot)

Here Cassatt shares a similar technique of suggesting rather than showing what the young woman is wearing, less concerned with the mechanics of the dress’s charm than with the overall, well, impression of it, another private moment caught on canvas, woman-to-woman.

Did the Impressionist’s bring on Fashion Week?

All together these women of different classes, the painters and the painted – each one stylish according to her means – have contributed to create a feminine archetype that lives on today : la Parisienne.

Theodore Child, an American art critic in Gilded Age Paris, spoke of the female residents of the capital:

“These women made a study of elegance and a profession of beautiful appearance more complete and more intelligent, perhaps, than any of the daughters of Eve who preceded them on the face of the earth, and they achieved a perfection of harmonious bearing, an originality ot composition, a stylishness, a chic, to use an accepted term, which has not yet been surpassed. The secret of this chic lies partly in the peculiar genius of the Parisienne. and partly unfailing application, and the striving after absolute elegance and fulness of pleasurable life in conditions of material beauty.”

The Parisienne collectively made Paris the fashion capital as we know it today, ready to receive the couturiers, heirs to Worth and the other great names that clothed the rich and famous, as well as the forgotten garment workers whose anonymous talent and flair put the city on the map of la mode.

We welcome you here to indulge in all its glory!

Do Join Us and Find Out More

While this virtual stroll through the Orsay sheds light on a lesser known Impressionist preoccupation- that of the dynamics of contemporary chic, there is so so much more to the Orsay! If you’ve liked this presentation, you’ll love how we show the premier train station- art museum of the whole world on our guided tour! You’ll even learn why it’s a train station, and more than you ever even wondered about the artists and art with in its walls.

If it’s the world of those artists you’re most curious about, how and where they lived and created, a walking tour of Montmartre is what you want and we have just the thing! Come along with us and explore the very streets where Renoir and Monet walked and laughed and drank and danced! We’ll tell you the importance of nooks and crannies you could never discover on your own, and relish doing so.

If it’s a more immersive dip into bohemian society of the period that you’re after, we can take you back in time to a Montmartre of its heyday, in which can-can dancers show you their world as they lived it!

Thank you so much for taking the time to read our blog! We are a small Paris-based tour company that prioritises a boutique personal experience where we can share our passion for our heritage and community with every individual that joins us. If you'd like to take a tour then head over to our website for an unforgettable trip to the city of lights. Also, check out our social media @memories.france for everything you could need to know for coming to Paris: from how to use the metro to coffee shops closest to each major monument, there is something for everyone!

Angelissa, Siobhan & the Memories France Family

If you're looking for more tips, itineraries, and insights into Paris, check out our social media!

- A Local’s Guide to the Covered Passages of ParisStep off Paris’s busy streets and into its hidden arcades — the covered passages. Built in the 19th century, these elegant glass-roofed galleries were once the city’s chic shopping streets, filled with boutiques, cafés, and charm. Today, they’re perfect for wandering, discovering artisan shops, and enjoying quiet meanderings away from the crowds. From Galerie Vivienne to Passage Choiseuil, each passage has its own story and treasures. This guide will show you the must-see passages, hidden gems, and local tips so you can explore Paris like a true insider.

- Did Marie Antoinette Really Wear a Boat In Her Hair?Marie-Antoinette’s hairstyles were far more than extravagant fashion statements. Towering poufs crowned with ships, symbols, and allegories turned her hair into a stage for politics, patriotism, and royal image-making. From naval victories to coded messages about power, fertility, and loyalty, the Queen’s hair told stories that eighteenth-century audiences knew exactly how to read—long before scandal reduced them to caricature.

- Secret Christmas Walks in Paris: 6 Magical Neighbourhoods to Explore this WinterParis sparkles at Christmas — but the real magic lies beyond the big boulevards. Let us take you into the authentic neighbourhoods of our city and show you the charming, local side of Paris during the winter holiday season. Bundle up, leave the tourists behind and follow us!

- Explore Paris with Kids: Track Down the Space InvadersHunting for Space Invaders in Paris is one of the most unexpectedly fun ways to explore the city — especially with kids. These colourful tile mosaics turn Paris into a giant treasure hunt, encouraging everyone to look up, wander slowly, and discover surprising flashes of street art on rooftops, bridges, and tucked-away corners. Download the free Flash Invaders app and let the adventure begin!

- Did Marie Antoinette Really Say "Let Them Eat Cake"? The Truth Behind the MythDid Marie-Antoinette really utter the infamous words ‘Let them eat cake’? In this post, we separate fact from fiction and explore how a myth grew to define the Queen’s reputation. Discover the real story behind the legend, and why history remembers her so differently than the caricature suggests.